Early improvements effective in forecasting recent Nor’easter; future forecast model upgrades planned

As the Northeast digs out from this week’s blizzard, a new NOAA-led effort to improve the forecasting of such high impact weather events is reaching an important early benchmark. One of the first major improvements - upgrading the resolution of three global forecast models -- has already shown its effectiveness. One of these models, the newly upgraded Global Forecast System (GFS) model, provided one of the most precise forecasts of the track, intensity, precipitation, and distribution of the Nor’easter. The other research models provided important forecast information, as well.

“The Global Forecast System did remarkably well in the recent Nor’easter,” said Louis Uccellini, director of NOAA’s National Weather Service. “This is due to the recent improvements we’ve made to the GFS, including higher resolution, improved physics, and better access to new data. With the help of scientists at NOAA Research, we’re making improvements to all our models, and upgrading supercomputers to improve our ability to translate data into actionable information, and to produce more timely, accurate and reliable forecasts.”

By the end of January, the $13 million project called the High Impact Weather Prediction Project (HIWPP), funded by Congress in the wake of Hurricane Sandy, will have improved the resolution on the global forecast model operated by NOAA Research Earth System Research Laboratory and the model operated by the U.S. Navy.

Improving global models

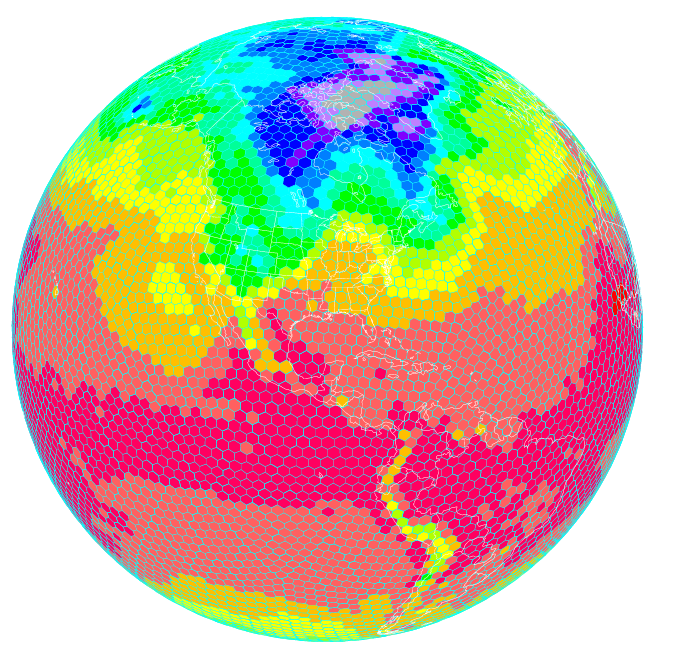

Scientists at NOAA’s Earth System Research Laboratory are running a high resolution global forecast model called the FIM, or Flow following finite volume Icoschedral Model. As depicted here, the FIM uses a unique grid that allows for a more uniform representation of the Earth. Higher resolution models are helping improve severe weather prediction. (NOAA)

In addition, NOAA researchers have written and installed programs to enable these three global models to work together effectively, which provides greater accuracy and confidence in forecasts. The third improvement is a plan to actively involve the broader weather forecasting community, including other public, academic and private sector scientists, in the evaluation of how these models work together to refine and improve forecasts.

“We are always looking for ways to improve the reliability and accuracy of our forecasts and models,” said John Cortinas, director of NOAA’s Office of Weather and Air Quality, who is overseeing HIWPP, which involves researchers from NOAA’s Oceanic and Atmospheric Research, NOAA’s National Weather Service, cooperative institutes, other government and academic partners.

“The goal of the project is to develop the next generation of weather forecast models that will eventually extend our ability to skillfully forecast high-impact weather out to several weeks and beyond,” Cortinas said. “By extending lead time for forecasts on storms like the one we’ve just experienced, cities and towns can better plan for these events, potentially saving lives and helping protect valuable land, homes and businesses. Businesses and industry can better plan everything from shipping to safe routing of air traffic to energy consumption. For ordinary citizens, it will be easier to plan an event or a trip.”

Over the last decades, weather forecasts have improved steadily so that we now have accurate forecasts out to five days, with reasonable accuracy to seven days. “We’ve gained about a day a decade in accuracy,” said Timothy Schneider, a research meteorologist at NOAA’s Earth System Research Laboratory, who is working to improve global forecast models. “Gaining a day of accuracy involves a combination of improving the science, adding computer power and increasing the necessary observations. With this project, we’re trying to accelerate this progress to make quicker gains.”

Global weather data key to improved local forecasts

“We know we can get better weather forecasts by improving the resolution of global forecast models so they depict weather in finer and finer detail,” explained Schneider. The resolution of NOAA’s two global forecast models has improved from grids that are 24 kilometers, to ones that are about 13 kilometers. “The finer you chop up the picture, the more you can see of what is happening inside a particular storm. This helps us make better forecasts.”

“If we’re going to predict weather out beyond seven and 10 days, we need even better global weather forecast models that show us what’s occurring on the other side of the Earth,” added Schneider. “Weather patterns on one side of the globe travel around the Earth and evolve. Storms born in the western Pacific follow air patterns that can create major winter storms on the West Coast, and weather patterns off the coast of Africa can spawn hurricanes in the U.S.”

Source: NOAA

As the Northeast digs out from this week’s blizzard, a new NOAA-led effort to improve the forecasting of such high impact weather events is reaching an important early benchmark. One of the first major improvements - upgrading the resolution of three global forecast models -- has already shown its effectiveness. One of these models, the newly upgraded Global Forecast System (GFS) model, provided one of the most precise forecasts of the track, intensity, precipitation, and distribution of the Nor’easter. The other research models provided important forecast information, as well.

“The Global Forecast System did remarkably well in the recent Nor’easter,” said Louis Uccellini, director of NOAA’s National Weather Service. “This is due to the recent improvements we’ve made to the GFS, including higher resolution, improved physics, and better access to new data. With the help of scientists at NOAA Research, we’re making improvements to all our models, and upgrading supercomputers to improve our ability to translate data into actionable information, and to produce more timely, accurate and reliable forecasts.”

By the end of January, the $13 million project called the High Impact Weather Prediction Project (HIWPP), funded by Congress in the wake of Hurricane Sandy, will have improved the resolution on the global forecast model operated by NOAA Research Earth System Research Laboratory and the model operated by the U.S. Navy.

Improving global models

Scientists at NOAA’s Earth System Research Laboratory are running a high resolution global forecast model called the FIM, or Flow following finite volume Icoschedral Model. As depicted here, the FIM uses a unique grid that allows for a more uniform representation of the Earth. Higher resolution models are helping improve severe weather prediction. (NOAA)

In addition, NOAA researchers have written and installed programs to enable these three global models to work together effectively, which provides greater accuracy and confidence in forecasts. The third improvement is a plan to actively involve the broader weather forecasting community, including other public, academic and private sector scientists, in the evaluation of how these models work together to refine and improve forecasts.

“We are always looking for ways to improve the reliability and accuracy of our forecasts and models,” said John Cortinas, director of NOAA’s Office of Weather and Air Quality, who is overseeing HIWPP, which involves researchers from NOAA’s Oceanic and Atmospheric Research, NOAA’s National Weather Service, cooperative institutes, other government and academic partners.

“The goal of the project is to develop the next generation of weather forecast models that will eventually extend our ability to skillfully forecast high-impact weather out to several weeks and beyond,” Cortinas said. “By extending lead time for forecasts on storms like the one we’ve just experienced, cities and towns can better plan for these events, potentially saving lives and helping protect valuable land, homes and businesses. Businesses and industry can better plan everything from shipping to safe routing of air traffic to energy consumption. For ordinary citizens, it will be easier to plan an event or a trip.”

Over the last decades, weather forecasts have improved steadily so that we now have accurate forecasts out to five days, with reasonable accuracy to seven days. “We’ve gained about a day a decade in accuracy,” said Timothy Schneider, a research meteorologist at NOAA’s Earth System Research Laboratory, who is working to improve global forecast models. “Gaining a day of accuracy involves a combination of improving the science, adding computer power and increasing the necessary observations. With this project, we’re trying to accelerate this progress to make quicker gains.”

Global weather data key to improved local forecasts

“We know we can get better weather forecasts by improving the resolution of global forecast models so they depict weather in finer and finer detail,” explained Schneider. The resolution of NOAA’s two global forecast models has improved from grids that are 24 kilometers, to ones that are about 13 kilometers. “The finer you chop up the picture, the more you can see of what is happening inside a particular storm. This helps us make better forecasts.”

“If we’re going to predict weather out beyond seven and 10 days, we need even better global weather forecast models that show us what’s occurring on the other side of the Earth,” added Schneider. “Weather patterns on one side of the globe travel around the Earth and evolve. Storms born in the western Pacific follow air patterns that can create major winter storms on the West Coast, and weather patterns off the coast of Africa can spawn hurricanes in the U.S.”

Source: NOAA

Post a Comment